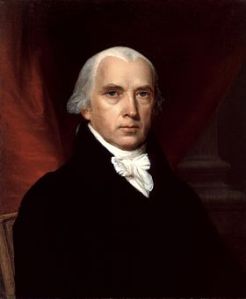

Born on March 16, 1751, in Port Conway, Virginia, James Madison was the son of James, Sr. and Eleanor Rose Conway Madison. He had three brothers and three sisters who lived to adulthood. James, Jr. wrote the first drafts of the U.S. Constitution, co-wrote the Federalist Papers and sponsored the Bill of Rights. He established the Democrat-Republican Party with President Thomas Jefferson, and became president himself in 1808. Madison initiated the War of 1812, and served two terms in the White House with first lady Dolley Madison. He died on June 28, 1836, at the Montpelier estate in Orange County, Virginia.

Born on March 16, 1751, in Port Conway, Virginia, James Madison was the son of James, Sr. and Eleanor Rose Conway Madison. He had three brothers and three sisters who lived to adulthood. James, Jr. wrote the first drafts of the U.S. Constitution, co-wrote the Federalist Papers and sponsored the Bill of Rights. He established the Democrat-Republican Party with President Thomas Jefferson, and became president himself in 1808. Madison initiated the War of 1812, and served two terms in the White House with first lady Dolley Madison. He died on June 28, 1836, at the Montpelier estate in Orange County, Virginia.

One of America’s Founding Fathers, James Madison helped build the U.S. Constitution in the late 1700s. He also created the foundation for the Bill of Rights, acted as President Thomas Jefferson’s secretary of state, and served two terms as president himself.

Born in 1751, Madison grew up in Orange County, Virginia. He was the oldest of 12 children, seven of whom lived to adulthood. His father, James, was a successful planter and owned more than 3,000 acres of land and dozens of slaves. He was also an influential figure in county affairs.

In 1762, Madison was sent to a boarding school run by Donald Robertson in King and Queen County, Virginia. He returned to his father’s estate in Orange County, Virginia—called Montpelier—five years later. His father had him stay home and receive private tutoring because he was concerned about Madison’s health. He would experience bouts of ill health throughout his life. After two years, Madison finally went to college in 1769, enrolling at the College of New Jersey—now known as Princeton University. There, Madison studied Latin, Greek, science and philosophy among other subjects. Graduating in 1771, he stayed on a while longer to continue his studies with the school’s president, Reverend John Witherspoon.

Returning to Virginia in 1772, Madison soon found himself caught up in the tensions between the colonists and the British authorities. He was elected to the Orange County Committee of Safety in December of 1774, and joined the Virginia militia as a colonel the following year. Writing to college friend William Bradford, Madison sensed that “There is something at hand that shall greatly augment the history of the world.”

The learned Madison was more of a writer than a fighter, though. And he put his talents to good use in 1776 at the Virginia Convention, as Orange County’s representative. Around that time, he met Thomas Jefferson, and the pair soon began what would become a lifelong friendship. When Madison received an appointment to serve on the committee in charge of writing Virginia’s constitution, he worked with George Mason on the draft. One of his special contributions was reworking some of the language about religious freedom.

In 1777, Madison lost his bid for a seat in the Virginia Assembly, but he was later appointed to the Governor’s Council. He was a strong supporter of the American-French alliance during the revolution, and solely handled much of the council’s correspondence with France. In 1780, he went to Philadelphia to serve as one of Virginia’s delegates to Continental Congress.

In 1783, Madison returned to Virginia and the state legislature. There, he became a champion for the separation of church and state and helped get Virginia’s Statute of Religious Freedom, a revised version of a document penned by Jefferson in 1777, passed in 1786. The following year, Madison tackled an even more challenging government composition—the U.S. Constitution.

In 1787, Madison represented Virginia at the Constitution Convention. He was a federalist at heart, thus campaigned for a strong central government. In the Virginia Plan, he expressed his ideas about forming a three-part federal government, consisting of executive, legislative and judicial branches. He thought it was important for this new structure to have a system of checks and balances, in order to prevent the abuse of power by any one group.

While many of Madison’s ideas were included in the Constitution, the document itself faced some opposition in his native Virginia and other colonies. He then joined Alexander Hamilton and John Jay in a special effort to get the Constitution ratified, and the three men wrote a series of persuasive letters that were published in New York newspapers, collectively known as The Federalist papers. Back in Virginia, Madison managed to outmaneuver such Constitution opponents as Patrick Henry to secure the document’s ratification.

In 1789, Madison won a seat in the U.S. House of Representatives, a legislative body that he had helped envision. He became an instrumental force behind the Bill of Rights, submitting his suggested amendments to the Constitution to Congress in June 1789. Madison wanted to ensure that Americans had freedom of speech, were protected against “unreasonable searches and seizures” and received “a speedy and public trial” if faced with charges, among other recommendations. A revised version of his proposal was adopted that September, following much debate.

While initially a supporter of President George Washington and his administration, Madison soon found himself at odds with Washington over financial issues. He objected to the policies of Secretary of Treasury Alexander Hamilton, believing that these plans lined the pockets of wealthy northerners, and was detrimental to others. He and Jefferson campaigned against the creation of a central federal bank, calling it unconstitutional. Still, the measure was passed by 1791. Around this time, the longtime friends abandoned the Federalist Party and created their political entity, the Democratic-Republican Party.

Eventually tiring of the political battles, Madison returned to Virginia in 1797 with his wife Dolley. The couple had met in Philadelphia in 1794, and married that same year. She had a son named Payne from her first marriage, who Madison raised as his own, and the couple retired to Montpelier. (Madison would officially inherit the estate after his father’s death in 1801.) But Madison didn’t stay out of government for long.

In 1801, Madison joined the administration of his longtime friend, Thomas Jefferson, serving as President Jefferson’s secretary of state.

He supported Jefferson’s efforts in expanding the nation’s borders with the Louisiana Purchase, and the explorations of these new lands by Meriwether Lewis and William Clark.

One of Madison’s greatest challenges played out on the high seas, with U.S. ships coming under attack. Great Britain and France were at war again, and American vessels were caught in the middle. Warships from both sides routinely stopped and seized American ships to prevent Americans from trading with the enemy. And the American crewmembers were forced into service for these feuding foreign powers. After diplomatic efforts failed, Madison campaigned for the Embargo Act of 1807, which prohibited American vessels from traveling to foreign ports and halted exports from the United States. Hugely unpopular, this measure proved to be an economic disaster for American merchants.

Running on the Democratic-Republican ticket, Madison won the 1808 presidential election by a wide margin. He defeated Federalist Charles C. Pinckney and Independent Republican George Clinton, securing nearly 70 percent of the electoral votes. It was a remarkable victory, considering the poor public opinion of the Embargo Act of 1807.

One challenge of Madison’s first term was growing tensions between the United States and Great Britain. There had already been issues between the two countries over the seizure of American ships and crews. The Embargo Act was repealed in 1809, and a new act reduced the trade embargo down to two countries: Great Britain and France. This new law, known as the Non-Intercourse Act, did nothing to improve the situation. American merchants disregarded the act and traded with these nations anyway. As a result, American ships and crews were still preyed upon.

In Congress, a group of vocal politicians started to call for a war against the British. These men, sometimes known as “War Hawks,” included Henry Clay of Kentucky and John Calhoun of South Carolina. While Madison worried that the nation couldn’t effectively fight a war with Great Britain, he understood that many American citizens would not stand for these continued assaults on American ships much longer.

The United States declared war on Britain in June of 1812. While his own party supported this move, Madison faced opposition from the Federalists, who nicknamed the conflict “Mr. Madison’s War.” In the early days of the war, it was apparent that the U.S. Navy was outmatched by British forces. Madison still managed to win the presidential election a few months later, beating out New York City Mayor DeWitt Clinton.

The War of 1812, as it is now known, dragged on into Madison’s second term. The conflict took a dark turn in 1814, when British forces invaded Maryland. As they made their way to Washington, Madison and his government had to flee the capital. British soldiers burned many official buildings once they reached Washington that August. The White House and the Capitol building were among the structures destroyed.

The following month, U.S. troops were able to stop another British invasion in the North.

And Andrew Jackson, though his soldiers were outnumbered, achieved an impressive victory over the British in the Battle of New Orleans in 1815. Both sides agreed to end the conflict later that year, with the signing of the Treaty of Ghent.

Leaving office in 1817, Madison and Dolley retired once again to Montpelier. Madison kept himself busy by running the plantation and serving on a special board to create the University of Virginia, with the help of Thomas Jefferson. The school opened in 1825, with Jefferson as its rector. The following year, after Jefferson’s death, Madison assumed leadership of the university.

In 1829, Madison briefly returned to public life, serving as a delegate to the state’s Constitutional Convention. He was also active in the American Colonization Society, which he had co-founded in 1816 with Robert Finley, Andrew Jackson and James Monroe. This organization aimed to return freed slaves to Africa. In 1833, Madison became the society’s president.

Madison died on June 28, 1836, at the Montpelier estate. After his death, his 1834 message, “Advice to My Country,” was released. He had specifically requested that the note not be made public until after his passing. In part of his final political comment, he wrote: “The advice nearest to my heart and deepest in my convictions is that the Union of the States be cherished and perpetuated. Let the open enemy to it be regarded as a Pandora with her box opened; and the disguised one, as the Serpent creeping with his deadly wiles into Paradise.”

Regarded as a small, quiet intellectual, Madison used the depth and breadth of his knowledge to create a new type of government. His ideas and thoughts shaped a nation, and established the rights that Americans still enjoy today.